Opinion: Onerous visa terms and poor service industry reduce Belarus’ efforts to attract tourists

With countless visa-free destinations to choose from, tourists of Western Europe and North America will choose to travel elsewhere unless Belarus improves its infrastructure and international repute.

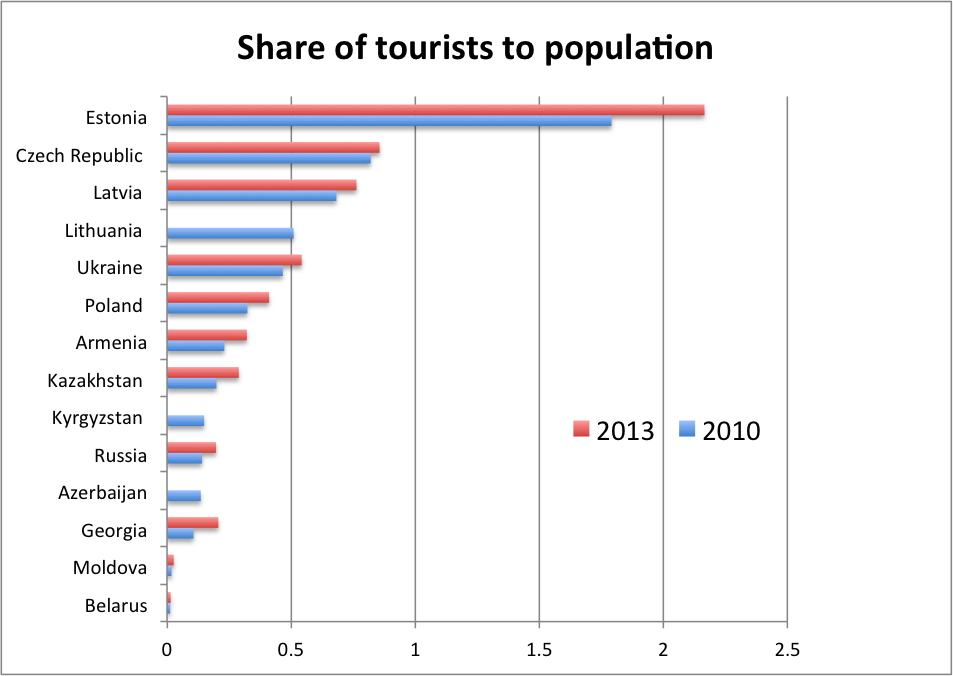

Belarus remains a blank spot on the map for many foreigners. A mere 137,000 tourists visited the country in 2013—twenty-one times fewer than the number who visited Estonia.

The world’s largest travel guide company, Lonely Planet, warns travellers that “visas are needed by almost everybody” and that “homophobia is rife.” VirtualTourist criticises the lack of customer service, the paranoia of locals, and the country’s “lunatic” president, Aliaksandr Lukashenka.

Belarus may have plenty of attractions, but many things have to change before the country can attract crowds of European tourists.

Given Belarus’s location in the heart of Europe, tourism could become an important source of revenue. With 28.4 million tourists, neighbouring Russia ranked as the ninth most visited country in the world in 2013, just after the United Kingdom.

But even among other post-Soviet states, Belarus ranks near the bottom in terms of tourism. Only Moldova, a country with a population 2.5 times smaller than that of Belarus, was visited by fewer tourists in 2013. According to the UNWTO, Belarus’s $722 million in international tourism receipts dwarfs in comparison to Ukraine ($5,083 million) and Poland ($10,938 million).

The many faces of Belarusan tourism

The web site of the Belarusan Ministry of Tourism praises the country’s pristine nature and rich wildlife. In November 2014, the Tour&Travel Warsaw 2014 travel exhibition showcased agro-tourism opportunities in Brest and Hrodna regions, in the southwest of Belarus. Hunting in Belarusan forests is also coming into vogue.

Visitors to Belarus have more diverse interests, however.

Source: UNWTO

Following the imposition of gambling restrictions in Russia in 2009, Minsk casinos began organising the so-called “Junket tours” for Russians, which include hotel arrangements, pickup at the airport or train station, and a plan of daily sightseeing and gambling activities.

Belarus’s reputation as “the last Soviet republic” also contributes to its charm among some tourists. The country is featured on web sites focused on travel to tragic death or disaster sites, such as Dark Tourism. According to the web site, “given the country's ‘pariah’ status, it’s kind of special.”

The human rights organisation “Belarusans in Exile” has instead used Belarus’s reputation as a dictatorship to undermine tourism. In 2013, the organisation published a cartoon of President Lukashenka welcoming visitors against a backdrop of police beatings. The organisation dared tourists “to experience dictatorship first-hand”.

But some tourists find Belarus’s conflicting narratives intriguing. “For a UK tourist, Belarus is a fascinating ‘other world’ destination,” said Jack Seaman, 29, of London, UK. Seaman said he would enjoy learning “how life in Belarus is and has been different to not only the West, but also to places like Poland, Ukraine and indeed Russia.”

A haven for Russian tourists?

Most tourists come to Belarus from Russia, the fourth largest outbound market in the world. In 2013, the country hosted 94,187 Russians, which is 31 times greater than the number of UK citizens, the second-largest group visiting Belarus. According to Belstat, Russian tourists contribute more than half of Belarus’s total income from tourism.

Thirty-one year old Moscow resident Anastasiya Pankratova has visited Belarus many times for tourism as well as business. She emphasises the country’s “tranquillity, open spaces, and order.” Belarus’s affordability makes it an attractive destination as well, according to Pankratova.

Image from globalpost.com uses UNWTO data

But there is a lot of room for improvement. “The catering industry is especially underdeveloped,” said Elena Babaeva, 35, a Muscovite who visited Belarus in summer 2014. “We were stunned when we learned that some cafes and restaurants are closed for lunch.” Babaeva recalled with frustration that she had to drive 150 km from the town of Braslav to Polotsk to replace a damaged contact lens.

Visa barriers discourage European tourists

Currently, only citizens from CIS states, Cuba, Macedonia, Montenegro, Qatar, Serbia, Turkey and Venezuela enjoy visa-free entry into Belarus. Western tourists who do venture into the post-Soviet space rarely bother to apply for a separate visa for Belarus. When obtained at Minsk Airport, the visa can cost up to $420 (for U.S. citizens), which exceeds the cost of a round-trip flight from most European destinations.

Iacob Koch-Weser, a 32-year-old resident of Washington DC, has travelled to Belarus several times for personal reasons. In 2011, he stood in a long line in “an understaffed and poorly managed visa office” in East Berlin. In the following years, he applied for a visa at the Belarusan embassy in Washington DC, where he noted far fewer visitors and applicants. He found the visa officer “a friendly young man who was willing to pardon slight hiccups in the paperwork, so long as it was nothing major.”

“There is a weird contrast between gaudy brochures advertising Belarus's tourist attractions on one hand, and on the other, a daunting list of requirements to acquire a visa, from invitation letters to medical insurance and an obnoxious visa processing fee,” Koch-Weser said. “So do they want people to visit or not?”

An additional hassle for foreigners whose stay exceeds three days is registering at the Belarusan Ministry of Migration. Administrative reasons for the imposition of this unusual additional requirement are unclear because foreigners already fill out a migration form when entering the country.

At the same time, the tourist infrastructure is underdeveloped. “It would have been helpful to see more English and Latin [script] writing in public spaces,” said Seaman, who visited Minsk in December 2014. He recalled that a Minsk tourist information office he visited was “taken by surprise” by his request for recommendations. “Though they did provide me with some useful information, it took a lot of prompting and patience from me,” he said.

Image from Katarzyna Rembeza

Many other destinations to choose from

In April-May 2014, Minsk waived visa requirements for the 2014 Hockey Championship. Some tourists purchased the hockey tickets – a condition for visa-free entry – but chose to occupy themselves with other activities.

One of them is Katarzyna Rembeza, a 27-year old market analyst from Warsaw, Poland, who instead went on a cycling trip.

“We took our tents but never used them because we were sleeping at people's homes. [...] Never before have I experienced such a level of hospitality!” she said.

According to Rembeza, while the visa is affordable (€25 for Polish citizens), collecting documents and standing in the line diminished her interest in travelling to Belarus. “The majority of Poles would probably tell you: 'why should we travel to countries with a visa requirement where we have so many non-visa countries to choose from?’” she explained.

Belarus has not only imposed more stringent visa requirements, but also dragged its feet on initiatives that could facilitate visits from abroad. One example is the 2010 Polish-Belarusan agreement on border crossings for people who live within 30 km from their shared border. Signed and ratified by the respective parliaments, the agreement was inexplicably stalled at Lukashenka’s desk.

For Belarusans, getting a visa is a precondition for visiting all but 22 states in the world. Despite high visa costs and humiliating procedures at the European consulates, Belarusans lead in the number of Schengen visas per capita. They have to apply multiple times per year because many EU states grant only one entry short-term visas to Belarusan citizens. For every international visitor into the country, about four Belarusans go abroad.

With countless visa-free destinations to choose from, tourists from Western Europe and North America will choose to travel elsewhere unless Belarus simplifies its visa procedures, modernises its tourist infrastructure, and improves its international reputation.

Originally published at BelarusDigest

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09