Influenced by Russian propaganda, Belarusans and Russians are finding more and more to share

While school textbooks in Belarus routinely emphasise the country’s location in the heart of Europe, on social media Belarusans themselves seem ambivalent, writes Volha Charnysh.

In February 2015 following the negotiations in Minsk the President of Belarus said he was not planning to “turn to the West.” He explained, “You and I are Russian people... we have shared history. We have shared opinions.”

According to the recently released World Value Survey (WVS), Belarusans and Russians indeed have a lot in common. Respondents in both countries perceive democracy as less important than respondents in West European states. They have become more religious in the last two decades and are much more focused on economic security.

Belarusans’ survey responses seem to reflect the quest for stability and aversion to political change inculcated by Russian and Belarusan media.

Headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, WVS consists of almost 100 nationally representative surveys conducted with nearly 400,000 respondents. In Belarus, the survey was administered by the Centre for Sociological and Political Researches at Belarusan State University.

Does democracy matter?

WVS results suggest that Belarusans differ from EU citizens most when it comes to politics.

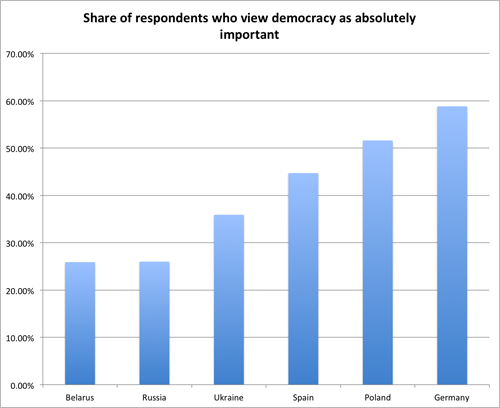

When asked to rank the importance of democracy on a ten-point scale, from absolutely important to not at all important, only a quarter of Belarusans chose the former. For comparison, nearly two thirds of German respondents and half of Polish respondents said democracy was absolutely important.

Both Belarusans and Poles were of low opinion about democracy in the 1990s. In the 1995-1999 survey wave, one fifth of respondents in each states strongly agreed with the statement “while democracy has problems it's better than any other form of government.” Over time, democracy has grown on the Poles, but not on their eastern neighbours.

The predominance of Russian-language media may be partly to blame. Belarusans watch Russian TV channels, surf Russian websites, and purchase Russian newspapers. State-owned channels tell them that democracy has already arrived in the post-Communist space and this democracy is of superior quality to the Western variety. In fact, even the Communist authorities used to call their political arrangement a "People's Democracy."

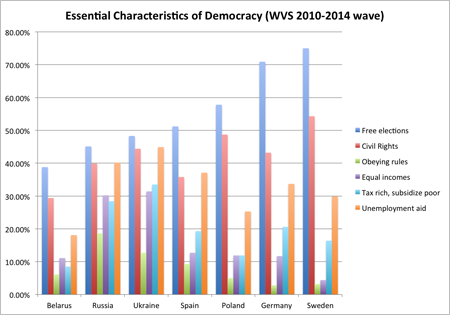

The meaning of democracy also varies across states. Relatively few Belarusans believe that choosing leaders in free elections constitutes an essential feature of democracy. Free elections are twice as important in Germany and Sweden, for example. Lukashenka would agree. In 2011 he told The Washington Post, “There is no less democracy in Belarus than there is in the United States.”

Furthermore, only 30% of Belarusan respondents said they believe that "civil rights that protect people’s liberty from state oppression" are essential for a democracy.

Interestingly, Belarusans concur with West-European respondents that democracy is not about equal incomes or soaking the rich. Perhaps due to greater inequality and conspicuousness of “oligarchy” in Ukraine and Russia, respondents from these states put more emphasis on economic redistribution.

Belarus on a conservative rebound?

As Maxim Trudolyubov noted in the February 2014 New York Times op-ed, religiosity is on the rise in the post-Communist states. WVS allows to compare religiosity between the 1981 and 2007 waves, as measured by the question on the importance of God.

Seven of eight states showing the greatest gains in religious faith are post-Communist: Russia, China, Belarus, Bulgaria, Serbia and Romania, Ukraine and Moldova. By contrast, religiosity has steadily declined in Western Europe. As Europeans grew richer, they went to church less and less.

Social scientists Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris explain the rise of religiosity in Eastern Europe by the combination of decreased economic and physical security and the collapse of Marxist ideology. Turning to religion in hard economic times, people in Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia are also reacting against the Soviet atheism policy.

The revival of religious faith has not gone unnoticed by the Belarusan state and opposition alike.

Imitating the Kremlin, Lukashenka frequently rails against the “degradation of Western morals.” For example, at the January 2015 Spiritual revival award ceremony, the President emphasised that “adherence to Christian values, morality, and aesthetic tradition is one of the main factors for the development of the Belarusan nation, preservation of its unity.” He described Belarus as an island of peace at the time when “the wave of international, inter-confessional conflicts and terrorist threats has engulfed the entire world.”

Some Belarusan opposition leaders seem to share Lukashenka’s sentiments. Vital Rymašeŭski of Belarusan Christian Democracy promotes “Christianity against Dictatorship” even as he rails against homosexuals. Paval Seviarynec of Malady Front in 2013 claimed that “the Bible is key to Belarusan National Idea” and in 2012 expressed concern about the “lost” believers from non-Christian traditions.

In contrast to Lukashenka, who calls himself “Orthodox atheist” and supports the Church in exchange for concrete political benefits, Rymašeŭski and Seviarynec are speaking their minds.

Growing religiosity makes Belarusans vulnerable to influence – not only from the Belarusan state or from conservative opposition leaders, but also from the Kremlin’s “Orthodox empire.”

Luckily, even as religious faith is experiencing a revival, it plays only a small role in Belarusan society. Only 16% of Belarusan WSV respondents viewed religion as “very important.” What is more, only 59% of Belarusans are Orthodox Christians. Religious pluralism as well as widespread atheism may be the surest bulwark against the encroachments of the “Russian world”.

Seeking economic security above all

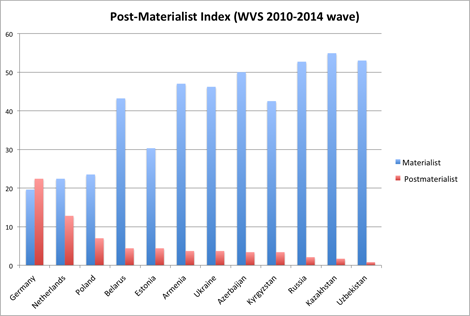

Social scientists have noted that respondents in post-Communist states differ from respondents in industrialised Western states in the predominance of the so-called survival (as opposed to post-materialist) values.

The survival values focus on economic and physical security. Once basic security needs are met, post-materialist priorities of self-expression and mental well-being come to the fore, according to Inglehart.

Post-materialist, liberal values have weak grounding in Belarusan society. Over 77% of Belarusan respondents, for example, viewed economic growth as their country’s most important priority, more important than, for example, “seeing that people have more say in how jobs are done in their communities” or than “making cities and countryside more beautiful.”

Preoccupation with material circumstances can be explained by the poor state of Belarus’s economy. As incomes rise, concerns about the quality of life, environmental issues, and human rights may begin replacing preoccupation with economic conditions.

East or West?

School textbooks in Belarus routinely emphasise the country’s location in the heart of Europe. On social media Belarusans themselves seem ambivalent. Some emphasise the country’s innate Europeanness and blame its current backwardness on Russian imperialism and Lukashenka’s leadership. Others rail against the depravity of the West and extol Belarus’s Slavic, Orthodox heritage.

Results from the recent WVS wave show what Belarusan and West Europeans have in common and what divides them. The Communist past and the authoritarian present have left a deep imprint on Belarusans’ attitudes and beliefs.

Out of step with their Western counterparts, Belarusans are becoming more religious, privilege economic security above other concerns, and remain suspicious of democracy. If Belarusans continue to consume Russian media, they and Russians will find more and more to talk about.

Originally published at BelarusDigest

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09