Belarusian identity reveals itself in transliteration of names

For many foreigners the Latinised spellings for Belarusian places and names continue to present real difficulties or just appear unpronounceable, writes Ryhor Astapenia.

Belarusians themselves feel annoyed about the ways their names are transliterated from Cyrillic into Latin script. It has become even more complicated with Belarus having two official languages - Belarusian and Russian.

Some people transliterate proper names in accordance with the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s or the Belarusian Academy of Sciences' standards, which was recently adopted by the United Nations. Most people and the media, however, are inconsistent when switching from one version to another. Despite the various approaches, one thing is clear - if one respects Belarusian identity, it is important to transliterate Belarusian names from the Belarusian language.

Confusing transliteration

How should one write the name of Aliaksandr Lukashenka, then? Is it Aliaksandr Lukashenka, Aliaksandr Lukashenka or even Aliaksandr Lukashenka? This is a point of confusion for many foreign journalists and researchers writing about Belarus. For instance, the respected British publication The Economist calls Belarusian leader Lukashenka and, alternatively, Lukashenka, while other Western major outlets use only Lukashenka.

Belarusians have their fair share of problems with transliteration, and sometimes use a different spelling of their names at different points. For example, Alexander Hleb, a former football player for Arsenal and Barcelona, switches between Hleb and Gleb.

Similar problems arise in writing out geographical place names. For foreigners it is difficult to grasp that Oktiabrskaja ploshad and Kashtrychnickaja polshcha refer to the same place. These are transliterated from two different languages - Oktiabrskaja from Russian and Kastrychnickaja from Belarusian.

The same is true with Hrodna (in Belarusian) and Grodno (in Russian) or Mahiliou (in Belarusian) and Mogilev (in Russian). Google Maps, for example, uses a bizarre mixture of various systems of transliteration in naming Belarusian geographical areas. Sometimes the names appear in Belarusian Cyrillic, sometimes in Lacinka, sometimes in Russian and whatever language is employed, they are not always used correctly.

Four ways to transliterate

Currently people use four different spellings of Belarusian names or cities: a transliteration from Russian, the spelling used by Belarusian Ministry of Interior, a random transliteration and the standard adopted by the United Nations. The first three fail to aptly convey the Belarusian language's designations and the fourth spelling is the single standard that Belarusian and foreign linguists recognise.

Transliteration from Russian is commonplace as Belarusians primarily use Russian in their daily lives. Also, many foreigners often perceive Belarusian culture and identity to be part and parcel of Russian culture. Moreover, many Belarusian leaders consciously use the Russian version of their names. For example, the Foreign Minister of Belarus Uladzimir Makei refers to himself as Vladimir Makei.

But Alena Kupchyna, Makei’s Deputy, transliterated her name from the Belarusian language in accordance with the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Belarus' standards. The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) also follows the same standards. ICAO, a UN specialised agency, only permits the usage of the English alphabet. These spellings often causes complaints as some people struggle to recognise their own surnames in their passport when they are written with this system.

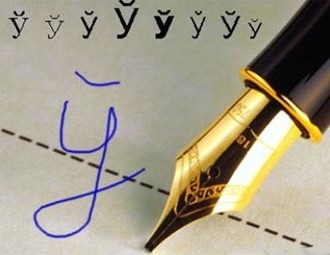

Those without prior knowledge would not know that the letter “h” stands for a “g” sound in Belarusian. For instance, the author’s name is pronounced something more akin to Ryhor than Ryhor. This explains why many people eventually choose to use other transliterations. George Plaschinsky, a Belarusian who changed the transliteration of his name, told Belarus Digest that he had previously written his surname as Plachtchinski, but few could remember it.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs uses the ICAO’s transliteration by default in Belarusian passports, although everyone has the opportunity to specify how to their name should be transliterated when applying for a passport. This opens the door for people from other nationalities to write their names in accordance with their languages. For example, Belarusian citizens of Polish nationality can write their names in passport in Polish. This is one thing that differentiates Belarus from Lithuania, where Poles cannot use the Polish variant of their name on any official documents. In Belarus one can even transliterate their name from Russian and keep their surname's Belarusian spelling.

Despite the fact that the Ministry of Internal Affairs makes it possible to transliterate one's name as you wish, this limits people to only English letters and excludes letters like š (sh) or č (ch). This makes it impossible to use the most appropriate spelling, one which was developed by the Academy of Sciences of Belarus and the United Nations, who adopted these Belarusian toponyms.

Historically the Belarusian language has used three modified alphabets - Cyrillic, Latin and Arabic - and with Latin being used in a very broad manner. For example, using this spelling Lukashenka would be transliterated as Lukashenka. Belarus Profile, a sister project of Belarus Digest, uses this version when writing out the names. The titles of Minsk streets and metro stations are written according to this standard as well. Even Google Translate can transliterate Belarusian language according to this system.

Is there a good solution?

For Belarusians, the question of how to write out one's own name continues to be a pestering problem. The author of this article once thought about changing his surname from Astapenia to Astapienia, which would bring it more in line with its proper pronunciation. Since many of his official documents were already issued to Astapenia, changing his surname could lead to mounds of bureaucratic hassle and problems down the road. That is why many Belarusians, not satisfied with the transliteration on their passports, continue to be reluctant to change it.

Despite all these problems, there is only one standard preferred by scholars with the Belarusian Latin alphabet. In 2000, the Institute of Language of the National Academy of Sciences established it as the foundation for the transliteration of Belarusian proper names in foreign languages.

However, this standard needs the support of the authorities' to allow it to be used in passports. It is already more or less the standard with Belarusian place names. According to this method of transliteration, Baranovichi will be Baranovichi and Statkevich will be Statkevich. The Journal of Belarusian Studies, the oldest English language double blind peer-reviewed periodical on Belarusian studies, follows this transliteration method.

Foreigners can use several styles to write Belarusian names, and they all depend on the situation in which they are employed. When it comes to official documentation, a passport helps them to skirt what could quickly become a bureaucratic hassle.

As for academic publications, it makes sense to use the transliteration of the Academy of Sciences as it is the most suitable system available. One can also ask how one should call a particular person - transliterating name from Russian by default can be even offensive to some Belarusians.

While it seems rather farfetched to develop a single unified system right now, it makes sense at least to exclude mostly blatantly incorrect versions - ones that use Russian transliterations. While few people inside Belarus use it, this is clearly not the best practise. Transliterating Belarusian names and places from Belarusian is a sign of respect towards Belarusians and their national identity.

Originally published at BelarusDigest

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09