Policy Brief “Language, Identity, Politics - the Myth of Two Ukraines”

This study is published within a series of policy briefs on Europe and its neighbours in the east and south on April 2014.

In this series we publish papers commissioned or produced by the Bertelsmann Stiftung in cooperation with regional partners in the framework of our work in this field This policy brief is the product of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s cooperation with the Warsaw-based Institute of Public Affairs (ISP).

The narrative of two Ukraines – the existence of two separate culturalpolitical communities within one Ukrainian state – has accompanied the relatively short history of independent Ukraine from the very beginning. Articulated by Mykola Ryabchuk more than twenty years ago and seemingly logical and reasonable, it has become the favourite narrative of many Ukrainian and international commentators and analysts. One of these Ukraines is pro-European, shares liberal democracy values, wants to join the European Union, “return to Europe” and, what is very important, speaks Ukrainian. The symbolic centre of this Ukraine is Lviv. The other is nostalgic about the Soviet Union, has close relations with contemporary Russia, is hostile towards the West and does not share “western” values. The language of this other Ukraine is Russian and its “capital” is Donetsk. Taking on board this narrative simply means equating one’s region of residence, political views, and preferred language.

Ryabchuk himself already repudiated this simplistic account some time ago. However, the tale of two Ukraines is still very popular and of- ten uncritically reiterated and exploited in political games. One could watch its new version after the eruption of protests against the suspension of signing of the association agreement with the EU by former president Yanukovich. Many commentators presented the battle for Maidan as a conflict between the Russian-speaking East and Ukrainian-speaking West. Currently, the same narrative is employed by president Putin, who justifies his intervention in Ukraine by the need to protect the “Russianspeaking” population against the allegedly nationalistic Ukrainianspeaking government and its chauvinistic supporters.

The tale of two Ukraines equates language, national identity, region of residence, and political orientation of all Ukrainian citizens. The available empirical data, presented in the text, demonstrates that there are indeed some correlations between the preferred language, region of residence, and political views, the perceptions of the neighbouring states as well as preferences as to the future of their country. However, the situation is far from being as unambiguous and unequivocal as the narrative of two Ukraines would suggest. Although the political attitudes of the populations of Lviv and Donetsk differ, it does not imply that the preferred language determines ethnic/national identity or geopolitical choices. The language situation is exceptionally complex, and the boundaries along which the linguistic dividing lines run are very blurred. What follows, the tale of two Ukraines, even though catchy and attractive, does not reflect the real diversity (linguistic, ethnic, or political) of Ukrainian society. It cannot justify the claim for the division or even federalisation of the Ukrainian state. What is more, irrespective of the region of residence, the majority of the population of Ukraine is sceptical of any divisions, including federalisation, of their country and believe that Ukraine is their only home country.

Language preference, region of residence, and national identity

The claim about two Ukraines can be easily invalidated by juxtaposing declarations about national identity, mother tongue, and the language used in everyday situations. These indicators are very differently distributed. A considerably larger percentage of the Ukrainian population speaks Russian than claims Russian identity. In other words, a large share of people who identify themselves as ethnic Ukrainians are Russophones. An analysis of the empirical data, indeed, illustrates certain tendencies: a larger share of “easterners” speak Russian, and “westerners” – Ukrainian. Yet, the linguistic situation is more complex. Depending on how the question about the language is worded we can even sometimes get diametrically different answers. What is more, the majority of Ukrainians are at least passively bilingual – even if they do not use one of the languages in everyday situations, they understand it perfectly well. It is not infrequent that while having a conversation, one person speaks Ukrainian and the other – Russian. Besides, especially in central Ukraine, many people speak socalled “surzhik”, a combination of Russian and Ukrainian. Yet, when asked about their reliance on surzhik, people may deny it and claim that they actually speak either Russian or Ukrainian. According to census results (2001),

68% claim that their mother tongue is Ukrainian and 30% – Russian. There are also considerable regional differences. In Lviv Oblast, for example, as many as 95% consider Ukrainian as their native language, whereas in Donetsk Oblast the figure is only 24%. Notably,

72% of the residents of the capital claim that their mother tongue is Ukrainian and only 25% that it is Russian.

Yet, when we ask about the language that respondents find easier to speak, the situation is somewhat different, and in Kyiv it is diametrically different. When we compare the census results and opinion polls, it turns out that a considerable share of Ukrainians consider Ukrainian their mother tongue, yet claim it is easier for them to speak Russian.

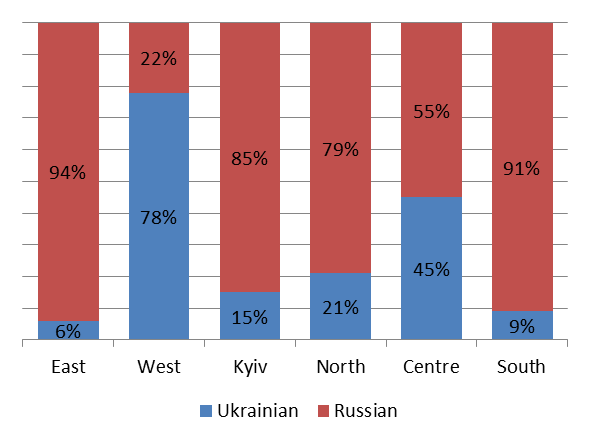

Graph 1. Language preferences of Ukrainians*

*The question was: “What language is it easier for you to communicate in?” Source: IPA opinion poll results, 20133

What is more, when respondents were given more options, the linguistic situation looks even more complicated. Except for the west of Ukraine, about 10% of the Ukrainian population admit speaking surzhik, and about 20% claim that they speak both Russian and Ukrainian at home, depending on the situation. It is also noteworthy that Russian is usually the preferred language of ethnic minorities. For example, Crimean Tartars predominantly speak Russian in everyday situations.

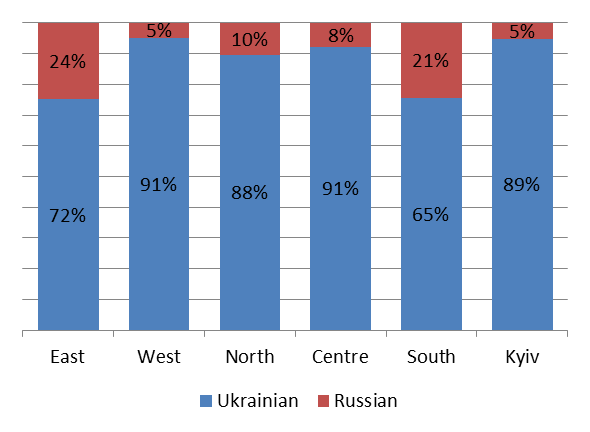

Graph 2. Language used in everyday conversations at home

.png)

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

The research results demonstrate that the preferred language is not equivalent to ethnic identity, which is particularly clear in the case of the population in the east and south of Ukraine. The juxtaposition of the poll results regarding language and ethnic identity demonstrates that a considerable share of people who prefer to use Russian in everyday life consider themselves Ukrainian. In the east, 72% claim to be Ukrainian, yet only 6% claim that it is easier for them to speak Ukrainian.

The situation in the south of the country looks similar.

Graph 3. Declared nationality – regional differences

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

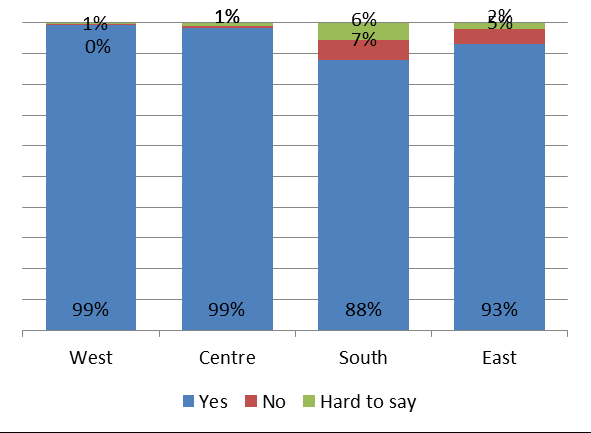

Notwithstanding any linguistic, political, or cultural differences, the vast majority of Ukrainians consider Ukraine their motherland. Even in the south of the country,

88% believe that Ukraine is their home country. This conviction is even more popular among residents of the allegedly pro-Russian east – 93% share this belief, in comparison to the traditionally patriotic west and centre (99%).

Graph 4. Do you consider Ukraine your motherland?

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

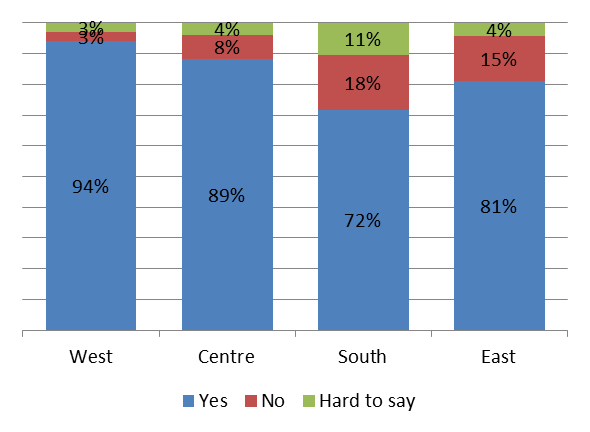

What is more, a dominating majority of Ukrainians demonstrate patriotic feelings for Ukraine. Only 18% in the south and 15% in the east do not consider themselves patriots of Ukraine.

Graph 5. Do you consider yourself a patriot of Ukraine?

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

In other words, even people who prefer speaking Russian and/or live in the east or south of the country still predominantly consider Ukraine their motherland and have patriotic feelings for their country.

There are some correlations between language preferences and region of residence on the one hand, and national identity and patriotism on the other, yet the results by no means justify the “two Ukraines” theory .

Language and values and attitudes towards democracy

According to the two Ukraines narrative, the Ukrainian-speaking population of Ukraine shares democratic values, and supports reforms strengthening civic freedoms and political rights, whereas the Russian-speakers are nostalgic about the Soviet Union and do not mind strong and centralised (authoritarian) rule. Does such a division exist in real life? We can check this on the basis of the results of the sixth edition of the World Value Survey – an opinion poll conducted in Ukraine in 2011 and 2012, i.e. during the presidency of Viktor Yanukovich.

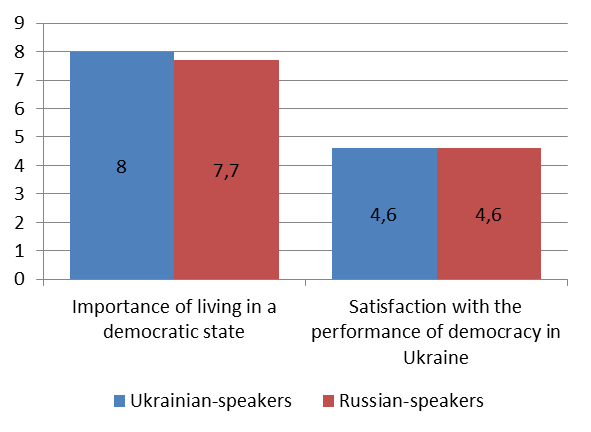

The respondents were asked to assess on the scale of 0 to 10 the importance of living in a democratic state. They were also asked about the level of satisfaction about the performance of democracy in their own country. The results demonstrate that there are no significant differences between Russianand Ukrainian-speakers regarding democracy. The majority of Ukrainians attached considerable importance to living in a democratically governed state and were very critical of the situation regarding democracy in their own country, irrespective of whether they were Russophones or Ukrophones.

Graph 6. Opinions on democracy as a principle and as practice*

*The respondents were asked to assess the importance of living in a democratic state as well as satisfaction with the performance of democracy in their own state on a scale of 0 to 10.

Source: World Values Survey: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/

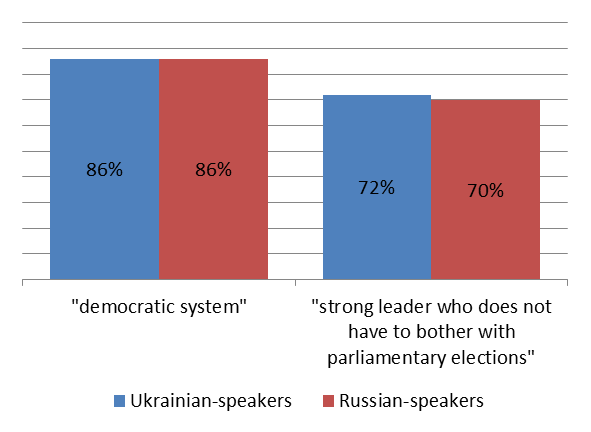

The respondents were also asked about their support for democratic and authoritarian forms of government. The juxtaposition of the results demonstrates the internal dilemma of Ukrainians who on one hand want to live in a democratically governed state, yet on the other – long for a single strong leader who will put their country in order. Yet, the difficulty in choosing either a democratic or an authoritarian form of governance was faced by both Russian and Ukrainian speakers alike. Needless to say, it results from dissatisfaction with the successive government brought to power as a result of (more or less) free elections.

Graph 7. Support for democratic and authoritarian forms of governance

Source: World Values Survey: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/

The views of the Russianand Ukrainian-speaking population of Ukraine do not differ considerably regarding their trust towards the authorities. People who prefer to speak Russian in everyday life only trusted the government under former president Yanukovich slightly more often – the difference with their Ukrainian-speaking fellow citizens was just eight percentage points. Slightly fewer people expressed trust in the parliament, with the difference between the two groups being just three percentage points.

Graph 8. Confidence in parliament and government

Source: World Values Survey: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/

The claim that Viktor Yanukovich and the Party of Regions, although disliked by the Ukrainian-speaking population, enjoyed widespread support and trust from Russianspeakers is easily refuted on the basis of these results. These results also demonstrate that we should not jump to conclusions that there are considerable differences in political attitudes between people according to linguistic dividing lines.

Language and region of residence and geopolitical choices of Ukrainians

So-called “multi-vector” orientation in terms of geopolitics – assigning relatively the same significance to relations with the EU and Russia – has been characteristic for both Ukrainian politics and the attitudes of Ukrainian society for the whole period of independence. It has always been difficult for Ukrainians to make a decided choice between the west and the east. The reasons for this state of affairs include the geographical position, history, assessments of (unfinished) systemic transformation after regaining independence, and the impact of the mass media.

The already cited IPA opinion poll (2013) demonstrates that the majority of Ukrainians would like to see their country intensively cooperating with both the EU and Russia. The dominant group, 42% of respondents, believed that intensification of relations both with the EU and Russia was in the interest of their state. However, among those who were able to make an unequivocal choice between the two geopolitical options, the supporters of the EU prevailed. Twenty-seven per cent believed that closer relations with the EU were in the interest of Ukraine, whereas the unequivocally Russian option was chosen by only 17%.

Graph 9. Opinions on closer cooperation with European Union

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

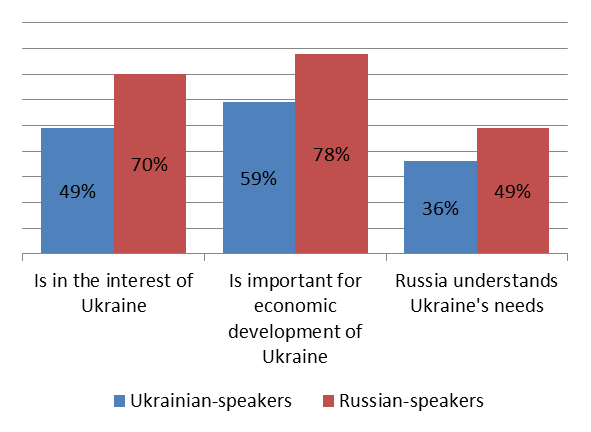

Graph 10. Opinions on closer cooperation with Russia

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

The majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of the language they speak, believed that closer ties with both the EU and Russia were important for the economic development of Ukraine. The majority of Russian-speakers and Ukrainianspeakers also believed that integration with the EU is in the interest of Ukraine. What is significant, however, is that not only did the majority of Russian-speakers believe that also closer ties with Russia were in the interest of Ukraine, but also almost half of the Ukrainian-speakers.

Thus, the “multi-vector” option was the most popular choice among the majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of the language they speak. Yet, when people were asked to make a choice between integration with Russia and integration with the EU, regional differences emerged. Predictably the west and the centre tended to choose the European vector of integration, and the east – the Russian one. What is significant, however, is that the residents of the south were divided in their opinions regarding geopolitical choices of their country – 45% wanted their country to join the EU, and 41% – to join the Customs Union of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus.

Map 1. Supporters of the Western and Eastern direction of integration – regional differences

.png)

73% supporters of the accession of Ukraine to the European Union

41% supporters of the accession of Ukraine to the customs union with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

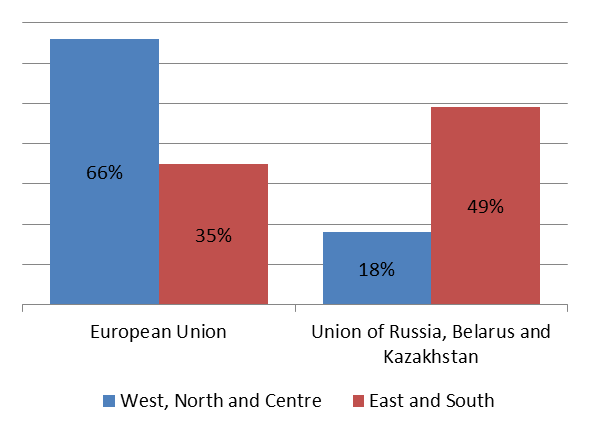

Graph 11. Supporters of the Eastern and Western vectors of Ukraine's integration – according to the two Ukraines claim

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

Graph 12. Supporters of the Eastern and Western vectors of Ukraine's integration – according to linguistic differences

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

An interesting tendency can be ob- served regarding the differences between the south-east and the centre-west. The latter is much more supportive of integration with the EU (66%) than the south-east is of integration with Russia (49%), whereas, irrespective of the preferred language, a larger share of Ukrainians preferred integration with the EU – 45% among Russophones and 62% among Ukrophones – than with Russia (40% and 16%, respectively).

Language and the perception of Poland

Poland is often perceived by both other EU member-states and its eastern neighbours as a country that strongly supports the pro-western and pro-European orientation of Ukraine. At the same time, in Russian propaganda, Poland is of- ten presented as a country that is trying to forcefully make Ukraine join the EU. According to the two Ukraines claim, thus, we could expect that the perception of Poland would be different depending on the language preferred and the region of residence of the respondents.

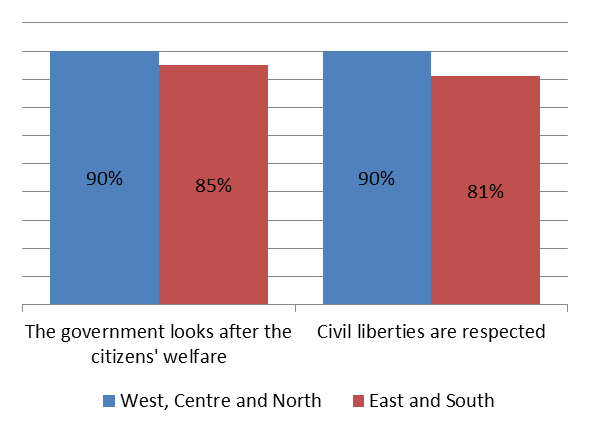

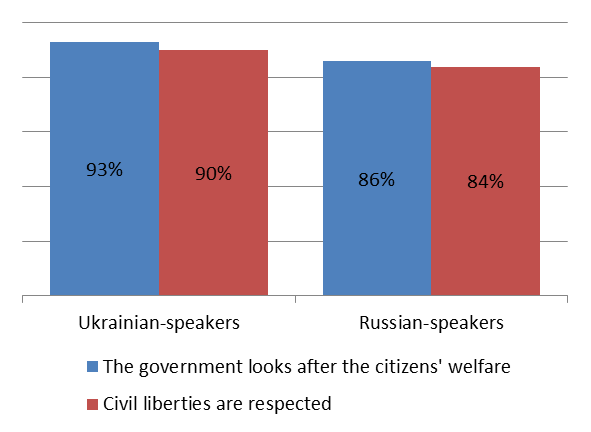

IPA research results demonstrate that Poland enjoys a very positive perception across Ukrainian society. Neither preferred language nor region of residence were of significance regarding the perception of how the Polish state functions. Both the population in the east and the west believed that the Polish government takes good care of its citizens and that Poles can fully enjoy their rights and civil liberties. Taking into account that Poland is an EU member state most frequently visited by Ukrainians, to a certain extent these results can be extrapolated to the whole of the EU.

Graph 13. Opinions on the situation in Poland – regional differences

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

Graph 14. Opinions on the situation in Poland – differences according to language preference

Source: IPA opinion poll results, 2013

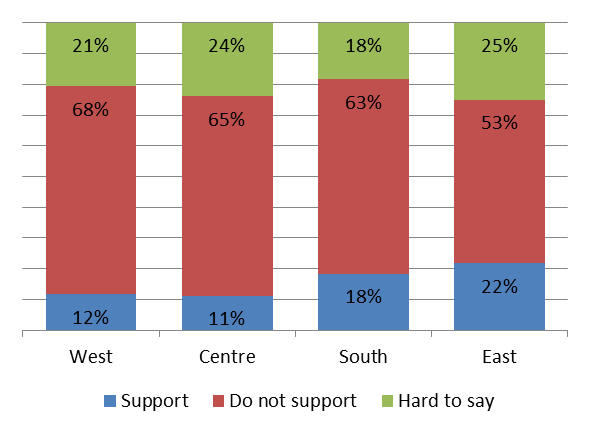

Graph 15. Support for the idea of Ukraine as a federal state

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

Region of residence and views on federalisation and separatism

The narrative about two Ukraines is often employed to justify the proposals for the political division of Ukraine, either federalisation or a split into two separate political entities, or uniting parts of Ukraine with another state (Russia). However, public opinion is predominantly hostile to any such changes, both in the west and in the east. More than half of the population in all the regions – with 53% in the east being the lowest score – are critical of the idea of the federalisation of Ukraine. This goes against the grain of popular perceptions about the widespread desire of eastern Ukrainians to see their region as part of a federation rather than the unitary state of Ukraine. What is interesting, about 20% (with some regional differences) find it hard to answer a question on the federalisation of Ukraine. These citizens are easy to persuade either one way or the other. In addition, many may simply want greater decentralisation of the state, and not federalisation.

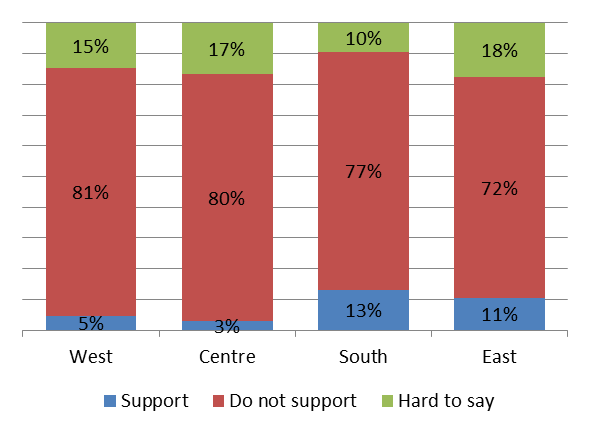

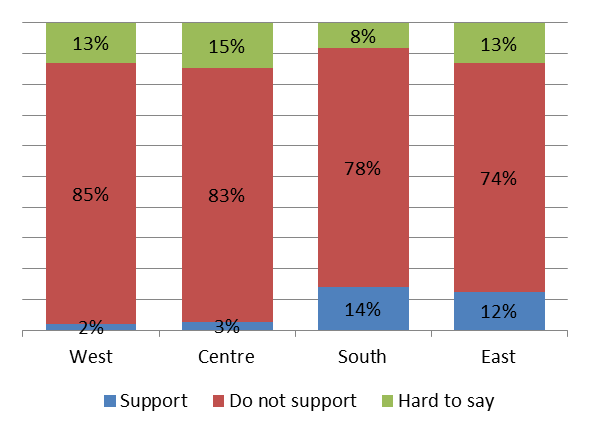

The idea of splitting Ukraine into two states enjoys even less support. More than 70% of Ukrainians in all regions do not support separating parts of Ukraine by creating a state covering the south-east regions. The greatest difference is between the east and the west, which is only nine percentage points.

Graph 16. Support for the idea of creating two independent states (the south-eastern oblasts vs. the western and central oblasts)

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

Separatist tendencies are not popular in Ukraine, irrespective of the region of residence. Only 5% in the east and 13% in the south would like their oblast to create an independent state, separate from Ukraine.

Graph 17. Support for separating one’s native oblast and creating an independent state

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

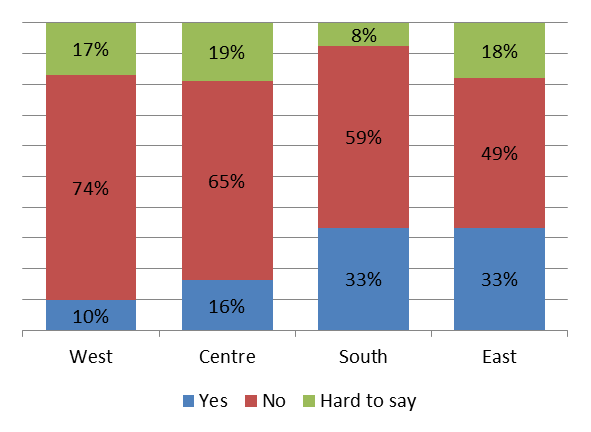

Joining Russia is almost equally unpopular. The vast majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of how close to Russia they live, does not want their oblast to join Russia – more than 70% in all regions. Forsaking Ukraine for the sake of Russia is popular among not more than 14% of the residents of the south-east. These results are especially significant in the face of the pseudo-referendum, engineered by the Russian authorities in Crimea.

Graph 18. Support for the idea of separating the south-eastern regions of Ukraine and forcing them to unite with Russia?

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

Finally, despite the fact that the research shows that regional differences between the east and the west are not that significant and do not justify the claim about two Ukraines, this narrative has become relatively popular also within Ukrainian society itself, especially in the east and south. One third of Ukrainians living in the east and south believe that the differences between the two parts of Ukraine are so significant that they may result in the division of Ukraine in the future. This conviction is considerably less popular in the centre and especially in the west – this opinion is shared by 16% and 10%, respec- tively. It appears that the impact of the Russian media is key here to understanding these regional dif- ferences. The Russian media have been promoting the idea of the “nationalistic” west that is so different from the east of Ukraine. As a result, the belief in some insurmountable differences between the easterners and westerners is twice as popular in the east as it is in the west of Ukraine. Yet, it is significant that despite such propaganda, the majority of Ukrainians, including the east and south, deny that a twostate solution is possible.

Graph 19. Belief that the split of Ukraine is possible due to irreconcilable differences between regions*

* The question was: “Do you believe in the existence of deep political contradictions, language and cultural barriers, and economic disparity between the citizens of the western and eastern regions of Ukraine that in future may result in the separation of these regions and/or the creation of separate independent states on Ukraine’s territory, or make those regions unite with other states?”

Source: Razumkov Centre, opinion poll results, 2013

Crimea – poles apart?

Once we have seen that the differences between the populations of the east and the west of Ukraine are not that considerable, the question arises whether Crimea is poles apart from the rest of Ukraine. It is often emphasised that Crimea only joined Ukraine in the 1950s and has never become really Ukrainian in spirit. Crimea is also the native land of the Crimean Tartars, who make up 16% of the peninsula’s population, according to the 2001 census.

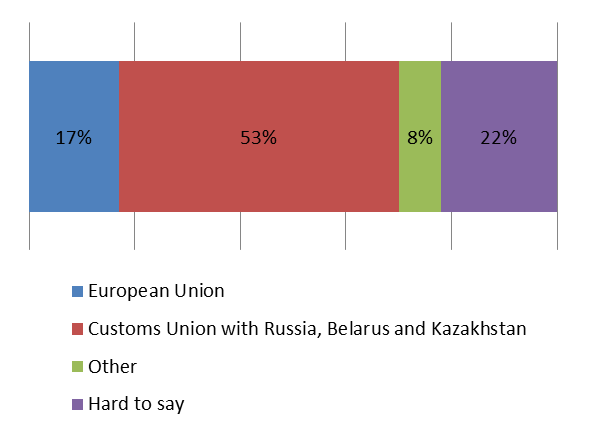

The Crimean population, comprising a considerable group of ethnic Russians who settled there during the communist times as well as families of the Black Sea Fleet members, is indeed much more favourably oriented towards Russia than towards the EU. According to the results of an opinion poll, conducted in Crimea in May 2013, similarly to the east of the country, 53% of the Crimean population would rather see Ukraine join the union with Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus than the EU (supported by 17%), if they had to make a single choice. It is also noteworthy that one third of the population did not support any of the two options.

Graph 20. Support for joining the European Union and the Customs Union with Russia*

* The questions was: “If Ukraine was able to enter only one international economic union, which entity should it be?”

Source: International Republican Institute,2013

Yet, as the results of the poll demonstrate, the population of Crimea neither felt that Russian speakers were in a disadvantaged situation, nor the majority wanted Crimea to change its country allegiance. The official motivation behind Russia’s military intervention and the following annexation of Crimea was the protection of its Russian-speaking population, allegedly suffering discrimination under Ukrainian rule. However, an opinion poll, conducted in Crimea in May 2013, demonstrates that only six per cent of the population claims that the status of the Russian language was one of the three issues most important to them personally.

What is more, the majority of the Crimean population supported the status quo – autonomy within Ukraine. Twelve per cent wanted to have Crimean Tatar autonomy – the percentage is close to the share of Crimean Tatars in the population of the peninsula, whereas annexation by Russia was supported by less than one-fourth of the population.

Graph 21. Opinions on the status of Crimea (in %)

Source: International Republican Institute, 2013

An even more recent opinion poll shows that although a rather considerable share of the Crimean population would like to see Ukraine and Russia join into one state, it is not the majority of the population. According to the results of the poll conducted in February 2014, several weeks before the referendum, only 41% believed that Russia and Ukraine should unite into one state.

It is likely that Russian media propaganda has convinced more people of the threats following the change of central government in Ukraine, and thus the support for separating Crimea from Ukraine and joining Russia has increased. Yet, it is hard to believe that Crimeans have changed their minds en masse within such a short period of time – according to the results of the Crimean referendum presented by the Russian side, more than 90% voted for joining Russia.

The analysis of the turnout dynamics during the referendum, the results of earlier opinion polls, the fact that Russian citizens were al- lowed to take part in the referendum, the boycott of the referendum by Crimean Tartars (12-16% of the population) and the turnout in some places exceeded 100%, all point to the fact that the results of the referendum have been considerably manipulated. What is more, there was no space for balanced information campaign showing pros and cons of joining Russia. The referendum was prepared within three weeks during a considerable political crisis in the country with the presence of Russian troops in the peninsula. A referendum under the barrel of a Kalashnikov can hardly be called free and fair.

All in all, the public opinion poll results show that Crimea is not significantly different from the rest of Ukraine and even the territorially modified version of the two Ukraines’ claim is not justified.

What is more, support for economic integration with the Russian-led customs union is not tantamount to separatist tendencies and the desire to become part of Russia.

Conclusions

It goes without saying that Ukrainian society is diverse in terms of language and culture as well as attitudes and opinions regarding the future of their state. However, all explanations based on the divisions according to language preferences are considerable simplifications and do not reflect the real situation, but rather impose preconceived notions, which are largely unfair to Ukrainians and dangerous in terms of the future of the Ukrainian state. Ukrainians may not agree on many issues, yet, Ukrainian society does not consist of two monoliths or two internally coherent cultural-political communities. Therefore, the widely-used category of “Russian speakers” is largely irrelevant as an explanation of socio- political divisions within Ukrainian society.

To sum up:

· Both ethnic Russians and Ukrainians often choose to speak Russian. Many Ukrainian patriots with strongly pro- western views may speak Russian at home and in everyday situations.

· Both Russian- and Ukrainian- speakers were strongly critical of the former president Viktor Yanukovich and the government of the Party of Regions. The majority of Ukrainians believe that close cooperation with both the European Union and Russia is in the interest of their state. Yet, when they need to make a single geopolitical choice, the majority prefer the European vector of integration, irrespective of the language they speak. Whereas, when people are forced to make a single choice between European integration and the Russia-led customs union, regional differences resurface. The population in the west and centre prefer the EU and the east prefers the Russian model of integration. Public opinion in the south is divided. Irrespective of the region of residence or the preferred language, the majority of Ukrainians would like to live in a democratic state. After several of years of Viktor Yanukovich’s rule, the majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of their preferred language, were critical of his presidency and the government of the Party of Regions.

· A decisive majority of Ukrainians also have a very positive perception of the situation in Poland. Irrespective of the preferred language or region of residence, Ukrainians believe that the Polish state take good care of its citizens and Poles enjoy their rights and civil liberties. The majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of the language they speak or the region they live in, do not share separatist sentiments. They do not support either the idea of creating two states or separating their region or oblast from Ukraine and making it independent or joining Russia. Support for close economic co- operation with Russia is not tantamount to the desire to join the Russian state in any region of Ukraine. Even in Crimea, less than one quarter of the whole population would like to see their region join Russia. The majority supported the status quo – Crimea being part of Ukraine and having an autonomous status. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians, irrespective of language or region of residence, consider themselves patriots of Ukraine and see Ukraine as their motherland.

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09