The Eurasian Economic Union: a one way ticket

On May 29, 2014, the leaders of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia signed an agreement on the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union.

It seems to be a significant event, but the story of integration initiatives in the post-Soviet space is so messy that it’s not easy to understand the how and why of things. Though, in the case our unchallenged helmsman has “entered” Belarus in this new interstate association, it wouldn’t be bad to understand what has this action meant and what it has threatened with our country and all of us, as well.

Sketch One, Historical

Since the collapse of the USSR, there have appeared several integration initiatives in its former space, non-viable in varying degree. The Belavezha Accords of 1991 made the Soviet Union disappear and have announced the beginning of the first attempt of reintegration on a new basis, in the form of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The attempt to save all the good things from the Soviet Union in the form of the CIS and to get rid of all the bad things without revising the grounds of the association and reflecting the new geopolitical realities was originally stillborn. Formality and futility of the CIS was repeatedly stated by its participants, but attempts to breathe life into it turned out to be useless.

The countries have tried to find more pragmatic forms of alliances. It resulted in a series of new integration initiatives: the Union State of Belarus and Russia (1997), the Eurasian Economic Community (2001), the Common Economic Space (2003), the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia (2007), the Eurasian Economic Union (2014). All these intertwined initiatives, by and large, neither lead to the realization of their declared goals, such as creating the common economic space, free trade zone, free movement of people, goods, capital, harmonization of national legislations, creating of general principles of finance and customs regulations, unified educational space, etc.

It is possible to single out of really working elements of this intricate system of Eurasian integration only common economic space of Russia and Belarus and the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, as well as the Common Economic Space (since 2010). These alliances have a real impact on the economies of its member countries.

Three questions arise: firstly, why have not all these initiatives been implemented? Secondly, why have the countries, despite the obvious failure, made new attempts to integrate? And thirdly, why did the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia get real content?

The answers to these questions lie in the understanding of the situation faced by the newly independent countries after the collapse of the USSR. In 1991, the former Soviet republics began their autonomous existence. It was necessary for the independent countries to settle all the issues of existence, beginning from challenges of geopolitical orientation, building their own political and economic models, domestic reforms of public administration, economic management, science, education, etc. All in all, the whole range of problems was reduced to the three main tasks:

- Desovietization, or reorganization of the entire system of political, economic and social relations. Actually, it was necessary to get rid of the non-modern forms of the Soviet organization of activities, including, for example, finance.

- Completing the nation-building processes. The countries were to reconstruct or build their own national institutions of governance. One can quote a Belarusan methodologist and philosopher Uladzimir Matskevich who figuratively described the situation as it was necessary for the countries to “grow own head” that had remained in Moscow after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

- Modernization, or ensuring compliance with the current challenges. In particular, the countries had to fit somehow in the new international relations system established after the collapse of the communist system. This implied, as well, solving issues of fitting in the globalizing world economy, trade diversification, technological re-equipment of production, etc.

Neither the Commonwealth of Independent States, nor the subsequent integration projects did not contribute to the solution of any one of these tasks. Russia tried to remain a regional leader, cultivating various forms of dependence of the former Soviet republics: energy dependence (oil and gas), infrastructure dependence (pipelines, economic ties of industrial complexes), informational dependence (Russian TV channels), military-strategic dependence (military facilities, Russian “peacekeepers” in zones of frozen conflicts).

Basically, it was Russia who initiated various integration projects, but the countries, rather, needed more independence from it; thus, the latter quite successfully sabotaged all sorts of initiatives, not being pragmatically oriented. The post-Soviet integration projects did not carry any advantage for the countries for a long time and so remained at best a set of ritual diplomatic events.

However, from the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union on, there have appeared new attempts of integration. Why? Firstly, the countries and regions of the former empire were connected by close ties of production and economic relations: raw materials regions were the basis for more industrialized centers, there was a common energy and transport infrastructure, common trade markets, related branches of production. Accordingly, the newly independent countries fell heir to all these ties which demanded proper maintenance, often even against the prospects for future development.

Secondly, Moscow remained a point of attraction, and all foreign policy actions were taken by the countries while watching the reaction of Moscow. Belarus, till the first crisis in the relations with Moscow (1999), did not have its own foreign policy in the post-Soviet space at all. Only being confronted by the contradictions of the Russian-Belarusan interests, Belarus tries to act independently in the foreign policy field, in the search of balance and points of impact on the Russian leadership.

Thirdly, nostalgia for the Soviet past and existence in a union with someone remained widespread for a long time among the elites and the society. The idea of a separate, independent state was perceived by many as a strange and slightly possible, while the collapse of the USSR was perceived as a tragic event. Thus, according to the Gallup poll, even in 2013, a significant number of respondents (on an average, 51% in 11 former Soviet republics) believe that the collapse of the Soviet Union brought more harm than good.

Fourthly, the authoritarian post-Soviet regimes experienced tensions in relations with the democratic West and were politically and ideologically closer to each other than to the space of a common Europe. Figuratively speaking, the past of the countries appealed for the unification, and their present and future resisted archaic forms of this unification.

Out of the entire set of integration projects, only customs initiatives have shown somehow their efficacy. The functionality of a common customs space is due to the fact that it has quite a clear technical nature (common border, common customs tariff, and distribution of revenues from customs duties) and, at the same time, partly contributes to progress in the modernization issues. Norms of the Customs Union and the Common Economic Space adopted many modern standards of international and European model (economic reporting, investments, banking regulation, intellectual property, phytosanitary measures, etc.). In addition, for Belarus, common customs space with Russia allowed to turn to huge advantage re-export of petroleum products which ultimately led to a significant diversification of exports. The European Union, which consumes the lion's share of the output of the Belarusan oil refining, has become the second trade partner of Belarus, and it has partially reduced the dependence of our country on the Russian market. As for Kazakhstan, its resource-based economy is in dire need of modernization, and the Customs Union and the Common Economic Space also provide opportunities for transfer of the modern Western norms and standards. Paradoxically, but, despite the anti-Western rhetoric of insidious Europe, the Eurasian integration is valuable only in those aspects that are ultimately related to the Europeanization and globalization.

Sketch Two, Political and Economic

The main difficulty in the understanding of the Eurasian Economic Union is that the visible processes and names used differ significantly from their essence and the main content. It all starts with the phrase “economic union” and “customs union” which in the normal sense belong to the sphere of economic relations between countries. However, applying purely economic pragmatists while analyzing Eurasian integration initiatives is meaningless, precisely because they are not what they seem. Models of existence, for example, of the free trade zone of the EU can hardly be applied to the understanding of what the Eurasian Economic Union is. The main distortion is introduced by ideological and political component of the Eurasian integration, as well as by non-traditional links between political and economic systems of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia.

Political regimes in all the three countries are variations of authoritarian dictatorships, and none of them can be described as fully functioning market economy. According to classification of the Bertelsmann Stiftung's Transformation Index (BTI), more liberal countries in economic terms, Kazakhstan and Russia, are among the countries with “market economy with functional exceptions”, and Belarus belongs to “poorly functioning market economy”. Functioning of the oligarchic economies of Russia and Kazakhstan is largely tied to power relations and is subject to political logic. The same thing is happening in Belarus, with the only difference that the policy of diktat in the economic sphere is provided by a super-centralized state system and the ruling group under the leadership of Lukashenko. Thus, political decisions, political pragmatism, interests of the ruling clans totally dominate the management of the economy and, consequently, they primarily guide the integration processes.

The Eurasian Economic Union is not an economic union of states, but the political and economic union of the ruling groups. In most post-Soviet states (with the exception of the Baltic states and, to some extent, Georgia and Moldova) have been established variations of parasitic authoritarian regimes whose main purpose is to maintain political power and control over the countries.

The regimes are guided by solving of the objective long-term development challenges (de-Sovietization, nation-building, modernization) only until these do not conflict with their overbearing aspirations. A peculiar system of corrupt exploitation of society, economic system and natural resources in the interests of the ruling clans is being established. Retention of power is based on the developed techniques of political manipulation of public opinion, alienation of citizens from the management system and social contract that means implies sufficient level of economic well-being of the population in exchange for political loyalty.

Such a system is generally ill-suited to long-term planning and is focused on short-term needs of the own survival. Economic unions are also used mainly for short-term benefits of ruling elites. The Belarusan government, for example, has learned well to benefit from the smuggling and speculations in the common customs space (it’s easy to remember examples of “schemes with solvents and diluting agents”, the case of Galina Zhuravkova and alcoholic speculations). There appears a kind of “authoritarian international” where the benefits of amorphous existence of the union exceed so far the losses from speculation on the forms of this union.

Being similar to the Belarusan political regime, the Russian one differs from national dictatorships also by the fact that it has been an empire. If for the Belarusan regime the space of its existence and ambitions is spread only on the very Belarus, the Russian regime is expansionary in nature. The logic of creation and functioning of the Eurasian Economic Union is, in addition, distorted by the ideological component of the recovery of “union of fraternal peoples” under the leadership and protection of Russia. Neo-imperial ambitions of Russia and its aspiration for expanding its influence on the post-Soviet countries brings to the common market yet another type of currency, shares of symbolic loyalty.

Belarus and Kazakhstan trade demonstration of allied status in exchange for certain benefits in relations with Russia. If for Belarus these benefits are purely economic in the form of gas subsidies, quotas for oil supply and cheap credits, then the situation with Kazakhstan looks a little more complicated. Kazakhstan is more economically independent, but its economy has basically raw character, and is thus in dire need of industrialization and modernization. Russia is possible solver for this problem by promoting transfers of modern Western technologies in Kazakhstan and, thus, Westernization of the country. In addition, the interests of the Kazakh oligarchs are intertwined with those of Russian oligarchs; Russia is the main channel of transit of Kazakh oil and gas to European markets, the Russian market is a major consumer of Kazakh goods, and Kazakhs are geopolitically interested in the external force capable of creating a counterweight to the growing influence of China. All this draws a rather complex picture of the political interest of Kazakhstan in cooperation with Russia.

With all successful and not very, attempts to benefit from the Eurasian Union, long-term interests of Russia and Belarus (we will not talk here about Kazakhstan) remains controversial. Russia is trying to restore in some form control over the post-Soviet space, and Belarus is seeking to gain as much independence and autonomy as possible. Herewith, even the Belarusan regime is interested in getting independence, as it wouldn’t be able to exist without this. Hence come the constant demands of Belarus and Kazakhstan for equality in the framework of the union relations and equally constant Russia’s attempts to ignore these demands.

Sketch Three, Economic

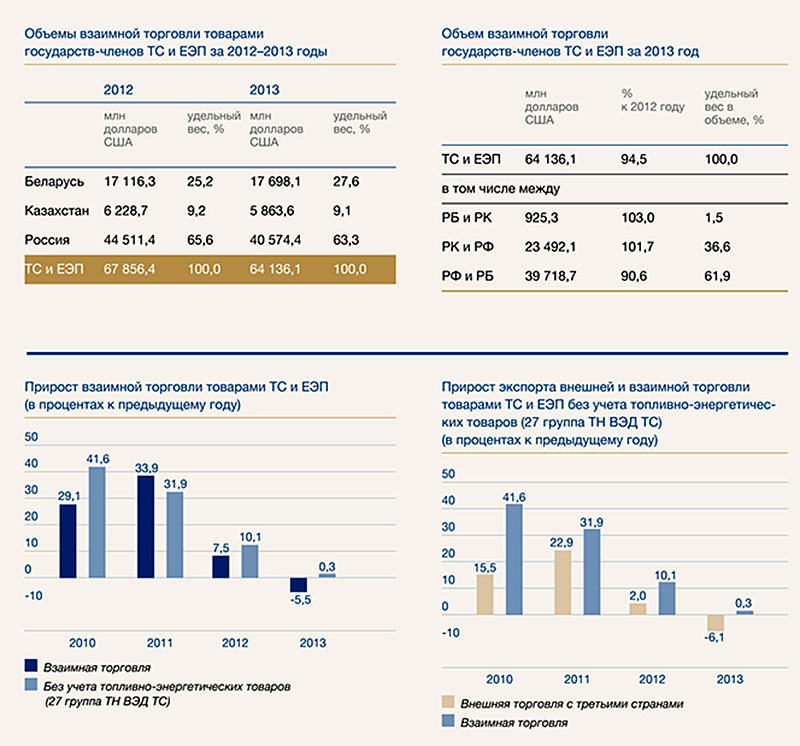

The fact that the countries and the political regimes are able to get short-term benefits from the existence of the Eurasian Economic Union should not mask the fact of its overall economic inefficiency and questionable long-term advantages. According to the Eurasian Economic Commission data, the volume of bilateral trade between the countries is decreasing.

Economic models of the countries largely compete with each other. Belarus is interested to maintain its industrial superiority and sell its products to the Russian and Kazakh markets, but the latter do not want to remain raw materials’ appendixes. Kazakhstan is committed to the industrialization and development of its own engineering through opening the truck assembly plants; subsequently creating problems for Belarusan MAZ and Russian KamAZ trucks through this. Russia wants to save the energy dependence of Belarus, but it does not want allowing the latter to enrich itself at the expense of re-export of petroleum products and indirect subsidization of production due to lower gas prices. Russian industrial centers compete with Belarusan enterprises in many commodity items (sugar, milk, meat, trucks, tractors, etc.), and it is not profitable for Russia to subsidize Belarusan production through reducing the cost of our products.

Among other things, in Belarus, many market segments are centrally managed and have oligopolistic nature (fish, alcohol, tobacco, furniture, sugar, etc.) This can be considered on the example of the meat and meat products market (one of the largest segments of the food market in Belarus). Belarusan meat market is controlled by Belarusan producers and is practically closed to outside vendors (there are only about 3.5%). This allows selling meat to the population at prices almost two times higher than the world market prices, getting monopoly rents and maintaining inefficient production, and hence the additional employment. Exports of the meat industry are mainly directed to Russia (96.7%, or almost 1 billion dollars in 2012). Having such a market structure, Belarusan state is absolutely not interested in letting anyone enter the market, including the Russian and Kazakh producers. Under the total state control, closing the entrance to the market is no problem at all for Belarus which uses a variety of administrative mechanisms of quotas, certifications, etc. Only naive foreign businessmen may believe that by launching production in Kazakhstan, they will automatically have access to the common market of the Eurasian Union. Such behavior, without the supreme political permission, will be regarded as a violation of the unwritten rules and appropriately sanctioned.

Non-market economies of the Customs Union countries can not be integrated at market-based principles; that implies that the economic logic can not be applied in the resolution of political and economic conflicts. Despite the signed agreement on the Eurasian Economic Union, “nowadays there remains a substantial gap between the adopted CU technical regulations containing new requirements, and national systems which ensure fulfillment of these requirements, such as accreditation, state control (supervision), responsibility and others that continue to operate “as of old”.

While the parties pretend that these differences can be eliminated in the process of implementation of the agreement, the sheer volume of non-resolved issues allows doubting it. In a common economic space, there move freely only 2/3 of bill of goods; only about one third of services is in free circulation; there are obstacles to the movement of agricultural products, problems in freight, etc., in the regulatory framework of the CU and CES there is about 800 seizure norms, restrictions and reference norms to national legislations. Solution of any sensitive issue will be transferred from the technical level of the Eurasian Economic Commission to the political level of heads of the governments and heads of the states. This all hardly makes the whole structure functional.

Remarkable stories of the customs duties on cars, “lacy linen”, duties on oil only added to the clear illustrations to this not very rosy picture. For Belarus, within the framework of the Eurasian Union, there are almost no visible long-term benefits. Credits of the EurAsEC Anti-Crisis Fund, oil and cheap gas only deepen the dependence of Belarus on Russia in the long-term run and impede the necessary structural reforms. In recent years, Belarus has lived in debt, but this can not continue indefinitely. The results of economic development of Belarus for 2013 seem to be very depressing.

“Imposition of structural problems on the unfavorable situation generates more medium and long-term challenges. For example, on the background of the lack of sources for growth and poor state of market, the risk of full-scale stagnation and the emergence of “poverty traps” increases (the outflow of the most skilled workforce on the background of low incomes that will reduce the potential for the long-term growth even to greater extent). In addition, possible new debts may lead to a situation of being burdened with debts in the near future, ie the current level of debt can be an obstacle for future growth”, wrote Dmitry Kruk in his policy paper, “The Belarusan economy in 2013: an attempt to “reset” the old growth model”.

Belarus is in vital need of large-scale structural reforms, but the Eurasian Economic Union can do nothing to help with it.

Sketch Four, Fantastic

While Belarus (or, more correctly, the Belarusan regime) will be paid for its economic expenses and repaid properly for symbolic shares of loyalty, it will exploit the Eurasian integration. What it threatens us?

1) Deepening economic dependence on Russia (“energy needle”, growth of public debt, privatization of the key productive assets in favor of the Russian capital).

2) Deepening foreign dependence on Russia. The number of shares of loyalty is not unlimited and Russia will require more. That has been seen in the reaction of Belarus at the Ukrainian events: rhetorical support of the integrity of Ukraine, but de facto Belarus has supported the Russian occupation of the Crimea.

3) Spreading the influence of pro-Russian forces in Belarus. Belarus, like Ukraine, has almost nothing to oppose the Russian information war.

4) Partial loss of autonomy in the economic policy sphere by switching control over customs, currency, financial regulation at the super-national level of the Eurasian Union.

5) Loss of the Belarusan sovereignty at moment when the costs of maintaining the Belarusan regime outweigh the benefits from the purchase of its symbolic loyalty.

The Belarusan regime will resist such a course of events, such as sabotaging its obligations under the union agreement, but its resistance resources are limited by economic inefficiency. Belarusan economy needs Russian subsidies, and these must be paid by the sovereignty. At the same time, continued existence at the expense of the Russian loans reduces the “volume” of the sovereignty. The way out of this vicious circle is in structural reforms and liberalization, but it creates a threat to the existence of the authoritarian regime of Lukashenko.

The prospects are not very bright, and the time to implement this scenario ends up within the horizon of 5-7 years. In light of these challenges, we can not count on the Belarusan regime as a guarantor of sovereignty, which highlights once again the issue of political changes in the country.

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09