Opposition parties retained their raison d'être, but pro-regime parties are losing their relevance

Belarus has no counterparts to the hegemonic political parties that emerged in other post-Soviet states, Volha Charnysh writes.

In Western democracies, parties exist to get politicians elected and help them implement policies. In Belarus, Lukashenka’s opponents cannot succeed at either of these activities. Even the political parties that do support the regime are only marginally more successful.

There are fifteen parties registered in Belarus; seven of them side with the government. These pro-regime parties sit on electoral commissions and local councils and claim to have the largest combined membership base. At the same time, very few Belarusians can remember their names -- and not a single pro-government party has begun to campaign for the 2015 presidential election.

Are these pro-government parties even real? Several pro-regime parties exist only on paper; their “members” help fill out electoral commissions ahead of any election to control the outcome. Some pro-government parties harbour greater ambitions, but lack a coherent ideology and strong leadership. One is so far from the understanding of normal politics, that it even lacks a web site.

No ruling party in Belarus

Belarus has no counterparts to the hegemonic political parties that emerged in other post-Soviet states. For example, Vladimir Putin’s United Russia holds 52.89% of seats in the State Duma and in 2012 reported 2,113,767 members. The New Azerbaijan Party, formed by former President Aliev in 1992, and now led by his son, has consistently won the largest share of seats in the parliament and in 2009 celebrated its 500,000th member.

In Belarus, even pro-Lukashenka parties cannot boast electoral success. The best performing party, the Communists, placed three deputies in the 110-seat Lower House of the Parliament in the 2012 elections. Seventeen party members were appointed to the 64-seat Upper House. The Liberal Democratic Party claims to have the largest membership base (45,866 members), yet won no seats in the legislative bodies in 2014.

The absence of a ruling party is good news for Belarusians, as it can prolong the survival of an authoritarian regime. The president has traditionally maintained that parties should not be created artificially by the government and that Belarus does not need a ruling party. In January 2014, however, he hinted at a meeting with district executives that a hegemonic party could help execute policies at the local level.

Pro-government party facades

Some parties exist purely to see that the regime’s objectives are carried out. For these parties, winning votes is not on the agenda.

The Belarusian electoral code requires that party and movement representatives make up a third of the membership of electoral commissions. As Vitaly Ruganin of Euroradio suggests in an article about the 2014 election, some pro-regime parties function exclusively to help the regime comply with the electoral laws and control election outcomes.

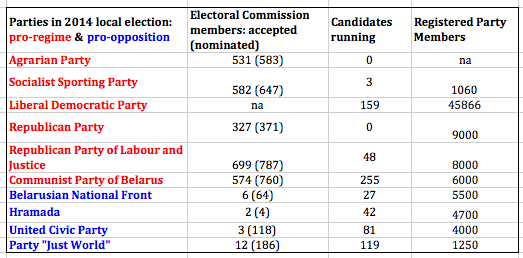

For example, in the 2014 local election, the Agrarian party offered no candidates, but sent 531 of its members to sit on electoral commissions. Similarly, candidates from the Republican Party did not run in the election, but 327 of them sat on electoral commissions. The Belarusian Socialist Sports Party offered up three deputies, though 582 of its members sat on electoral commissions. By contrast, the opposition party Belarusian National Front had 27 candidates running and proposed 64 committee members, of which only six were accepted. Parties created solely to stuff electoral commissions with pro-regime support lack incentives to invest in organisational infrastructure or even to create an online presence. The Agrarian party, for example, does not even have a web site, while the Republican Party’s web site has not been updated since 2005.

The party that seems to have grown fastest in recent years is the Republican Party of Labour and Justice. Whereas it lacked voblast (province) branches in 2006, it now has representatives not only in all six voblasts, but also in nearly all rayons (districts) of the country. The party’s regional leadership counts several directors of state enterprises and heads of regional administration among its ranks, which may allow it to easily collect signatures and recruit new “members.” In the 2012 parliamentary elections, seven out of its eleven candidates represented state and private business interests.

Chairing a pro-government party

At the helm of many pro-governmental parties stand former apparatchiks and red directors. Former red director, Vasily Zadnepranyi, who in 2009 sat on the Consultation Committee of the Presidential Administration, chairs the Republican Party of Labour and Justice.

The party’s Deputy Chair Aliaksandr Stsiapanau began his career by working for the Administration of Frunzensky District of Minsk. He received several thank you letters from Lukashenka for his active participation in the 2006 and 2010 elections. The party’s leadership also includes Babosov Eugenie, the Head of the National Academy of Sciences.

Siarhei Haidukevich, the chair of the Liberal-Democratic Party since its founding in 1995, has served in a number of leadership roles in the Soviet military establishment. In 2001, Haidukevich ran for president, winning 2.5% of the vote. Haidukevich congratulated Lukashenka with his victory. Then, in the 2010 election, Haidukevich collected the 100 thousand signatures necessary for registration to run again but then withdrew from running, calling the elections “a farce in which respectable politicians should not take part.”

There are times when pro-government parties not only criticise the lack of political competition in Belarus, but also contradict Lukashenka’s policies. For example, unlike the President, the Republican Party of Labour and Justice has recognised the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as well as the annexation of Crimea.

Twenty years without competition

Belarus’s political landscape has not always been so dire. In the 1995 Supreme Soviet, 105 deputies represented sixteen political parties, and 93 were independents. The Agrarian party who has no online presence today, received 34 seats in 1995. The Communist party that secured seats for three of its candidates in 2012, got 44 seats in 1995.

Twenty years of authoritarian rule seems to have undermined not only the opposition parties, which have suffered from repression, but also the pro-regime parties, which have functioned in a relatively friendlier environment. And while the opposition parties such as the Belarusian National Front have retained their raison d'être, the pro-regime parties are losing their relevance.

Belaya Rus, a pro-government association with 147,000 alleged members, chaired by the Minister of Education, may soon take their place. At the moment, its legal status as a republican association rather than a political party may allow for greater flexibility in recruitment and activity planning, though this may soon change.

In contrast to the pro-regime parties, Belaya Rus has already started preparing for the upcoming presidential election. The association created a republic-wide headquarters to coordinate campaign efforts by its local-level units and will provide observers and help staff electoral commissions.

The rise of Belaya Rus, as well as the parallel growth of pro-opposition movements such as Tell the Truth, suggests that broad non-ideological movements better fit Belarus's current political realities than political parties. Parties, on the other hand, may become increasingly obsolete as they do not participate in government and lack citizens' trust.

Originally published at BelarusDigest

-

03.01

-

07.10

-

22.09

-

17.08

-

12.08

-

30.09